Itinerary edited by UNIVERSITY OF DI PERUGIA

In 1477, Luca Pacioli, a friar from Sansepolcro who would over the following decades permanently change the structure and quality of the teaching of mathematics in the Umbrian city, was summoned to Perugia to teach arithmetic. Pacioli was born in Sansepolcro between October 1446 and October 1448. During that period, Piero della Francesca had a shop in Sansepolcro, who, along with Melozzo da Forlì, is remembered for his studies and results in perspective painting. The young Pacioli was most certainly first introduced to the mathematical theory of perspective in that shop, a subject that he was able to study and learn more about during the years he frequented Leonardo, Leon Battista Alberti, Melozzo da Forlì and Marco Palmezzano, but also Bramante, Francesco di Giorgio Martini, Giovanni Antonio Amadeo and perhaps AlbrechtDürer. Pacioli soon left Sansepolcro for Venice, where he had the opportunity to work for the merchant Antonio Rompiasi, also taking care of his three children’s education while he furthered his own studies in mathematics with Domenico Bragadin at the famous Rialto School. In 1470, he dedicated a treatise on algebra and arithmetic, then lost, to Rompiasi’s children. He later moved to Rome, living for several months in the house of Leon Battista Alberti, who not only gave him maths lessons but also a good religious education. His passion for religion culminated in 1475, when Pacioli donned the Franciscan habit of the Friars Minor Conventual, which can be found in his famous portrait in the Art Gallery of the Capodimonte Museum in Naples.

After an undocumented period in Urbino, on 14 October 1477 the friar was asked to teach arithmetic at the University of Perugia for the first time, where he remained until 1480. It should be noted that the University of Perugia was founded in 1308 with a bull issued by Pope Clement V, but the first chairs of geometry, arithmetic and algebra were only established in 1389. Between 1481 and 1485, he taught in the then Venetian city of Zadar, returning to Perugia from 1486 to the April of 1488. This time Pacioli was away from Perugia for twelve years. Between 1488 and 1489 he got a job "in the worthy Middle School in Naples", which was followed by a brief period of teaching in Rome, where he frequented the Della Rovere family. In the residence of Giuliano, the future Pope Julius II, the Franciscan friar showed a few models of regular polyhedra (tetrahedron, octahedron, cube, icosahedron, dodecahedron) to Guidobaldo da Montefeltro, to whom he dedicated the work that rendered him famous: the “Summa de arithmetica, geometria, proportioni et proporzionalità”. In 1491 he returned to Borgo Sansepolcro, where he remained until 1493, after which he went back to Venice via Padua.

The Summa, published in 1494, is a great compilation of materials on arithmetic, algebra and Euclidean geometry, as well as double-entry bookkeeping, whose usefulness was proved over the years he worked in Venice. The six hundred pages contained in this work had a major influence on the diffusion of mathematical knowledge of that period. The work also contains a general treatise on algebra and arithmetic, which earned him an invitation from Ludovico il Moro to go to Milan, where, between 1496 and 1499, Pacioli took care of the wages paid by the Duke, under whom Leonardo da Vinci also worked for many years.

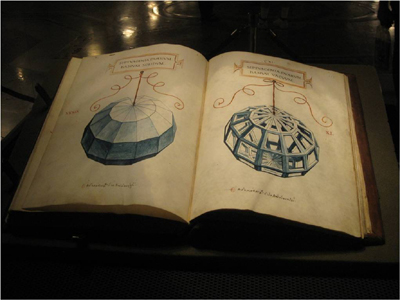

The two men therefore had the opportunity to get to know each other and work together. In fact Pacioli gave the Tuscan genius lessons in fractions, proportions and the work of Euclid, after which Leonardo painted the 60 illustrations of polyhedra, seen as solid forms in perspective, which make The Divine Proportion unique. This work was compiled in 1497, as a result of the interest Pacioli showed during the Latin translation of Euclid's Elements and of his study of Piero della Francesca’s manuscript “De Perspectiva Pungendi”. Several topics are addressed in the book: plane figures, with particular attention to the divine proportion, or the golden ratio; polyhedra and platonic solids; detailed studies on architectural art, with references to the ideas of Vitruvius and Leon Battista Alberti, and finally issues related to prospective. The treatise is rich in references to sacred texts and the Platonic Timaeus.

Although conceived during the years he lived in Milan, the three-volume work did not go into print until 1509.

During his stay at the Sforza court, Luca also taught at the Studium of Pavia (1498).

Pacioli left Milan for Florence with Leonardo, stopping in Mantua where he met Isabella d'Este, to whom he dedicated his treatise “De ludo Scachorum”, which contained over hundred chess problems.

In November 1500, Pacioli was once again summoned to Perugia, although he then returned to Florence, where he remained until 1506 (from 28 July 1505, he resided in the Franciscan monastery of the Holy Cross) teaching at the Studium of Pisa (moved from Pisa to Florence in 1497) .

During his stay in Florence he also taught at the Studium of Bologna (1501-02). In 1508, following a short stay in Rome, he returned to Venice, where on August 11th he gave a lecture on the fifth book of Euclid's Elements in the church of St. Bartholomew, and on December 19th of the same year he asked Doge Leonardo Loredan for the printing privilege for his works. Although granted, the privilege did not benefit his treatise “De viribusquantitatis”, compiled between 1496 and 1508 and containing lots of numerical, mathematical and topological games, riddles and puzzles, which remained unpublished.

He returned to Perugia for the last time in 1510 , and taught again in Rome in 1514. When he died in 1517 in his hometown of Sansepolcro, Pacioli had taught in a dozen cities and published volumes that have long remained reference books.

Although known for his surliness, his affection for this Umbrian town is demonstrated in the dedication of his first treatise on algebra and geometry in 1478:

«SuiscarissimisdiscipulisegregiisclarisqueiuvenibusPerusinis!».

Girolamo Bigazzini, disciple of Pacioli

Girolamo Bigazzini was one of Luca Pacioli’s Perugian disciples, and contrary to his master he spent his entire life in his hometown. He was born in 1480, in the family castle in Coccorano, Perugia. He first devoted himself to studying Latin, Greek, logic and philosophy, after which he focused on mathematics and geometry. His expertise in classical languages permitted him to study independently and, above all, to read texts by Boethius, Euclid, Vitruvius and others in their original language.

He met Luca Pacioli during one of his visits to Perugia, at the time when the fame of Pacioli ‘s “Summa de arithmetica, geometria, proportioni et proporzionalità” was beginning to spread. It was thanks to Bigazzini’s insistence that the City Council of Perugia commissioned Pacioli to exhibit his work (probably in 1500). It is unclear whether Bigazzini played a role in Studium of Perugia, but he made an important cultural contribution to the city.

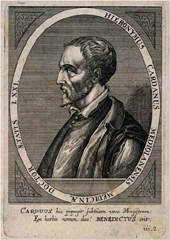

Sozii, one of his students, said that the reason Bigazzini stayed in his hometown was due to family ties, without which he would have travelled to European cities such as Krakow, Vienna, Nuremberg, Tübingen and Paris, homes to the most important mathematical and astrological centres.Bigazzini was also interested in astrology: this is demonstrated by his epistolary relationships with Girolamo Cardano  (doctor, astrologer and mathematician) and Luca Gaurico, an authority in the field of astrology. The only work he published with success was “Prognosticon year salutis 1523 et 1524”, which talks about the disputed conjunction of planets in Pisces in February 1524 that had led to concerns for a second universal deluge.

(doctor, astrologer and mathematician) and Luca Gaurico, an authority in the field of astrology. The only work he published with success was “Prognosticon year salutis 1523 et 1524”, which talks about the disputed conjunction of planets in Pisces in February 1524 that had led to concerns for a second universal deluge.

Between 1540 and 1543 he was summoned by Pope Paul III, who was in Perugia to ensure the continuation of building works for the Fort (later named Rocca Paolina after him), for lessons in astronomy and astrology. Girolamo Bigazzini died on 30 March 1564.

Between October 1446 and October 1448Born in Sansepolcro (at the time Borgo Sansepolcro)

1459 After the death of his father, he went to live with the Folco di Giovanni di Canti Bofolci family and sons Piergentile and Conte

In the mid-1460s, he moved to Venice and went to work for Antonio Rompiasi, a merchant on Giudecca

1470-1471 short stay in Rome, where he met Leon Battista Alberti

1477-1480 called by the Studium of Perugia

1481 moved to Zara

1486 stayed in Perugia

Between 1488 and 1489 he got a job «in the worthy Middle School in Naples»

1489returned to Rome to teach for the second time

1491-1493 returned to Borgo Sansepolcro

1494 returned to Venice to edit the Summa (dedicated to Guidubaldo da Montefeltro)

1496-1499 stayed in Milan where he frequented the cultured and stimulating court of Ludovico Sforza

1498 taught at the Studium of Pavia

1500 went back to teaching in Perugia

1501-02 also taught at the Studium of Bologna

1508 taught in Rome

1509 The Divine Proportion was printed in Venice

1514-1515 taught in Rome

Betweem 15 April and 20 October 1517He died in Borgo Sansepolcro (or perhaps in Rome)

Cities where he lived and worked

Venice

Venice  Rome

Rome  Perugia

Perugia  Zara

Zara  Naples

Naples  Padua

Padua  Urbino

Urbino  Milan

Milan  Pavia

Pavia  Florence

Florence  Mantova

Mantova  Bologna

BolognaCheccucci D. (2014/2015). Un Museo della Matematica: la Galleria di Matematica di Casalina. (Tesi di Laurea Magistrale in Matematica, Università degli Studi di Perugia).

Di Teodoro F. P. (2014). Pacioli, Luca. Consultabile sul sito web http://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/luca-pacioli_(Dizionario-Biografico).

Black E. M. (2013). La prolusione di Luca Pacioli del 1508 nella chiesa di S. Bartolomeo e il contesto intellettuale veneziano. In Bonazza N., di Lenardo I., Guidarelli G. (Eds.). La chiesa di S. Bartolomeo e la comunità tedesca a Venezia (p. 87-104). Venezia : Marcianum Press.

Rocco F. (2013). Leonardo e Luca Pacioli: l’evidenza. Nuove regole e nuove forme nel manoscritto di Luca Pacioli sul gioco degli scacchi. S.l., s.n.

Ughi E. (2013). Il poliedro di Leonardo. Come costruire un meraviglioso solido leonardesco. Perugia: Corsare.

Santoyo J. C. (2012). La autotraducción en la edad media. In Rubio Árquez M., D’Antuono N. (Eds.). Autotraduzione, teoria ed esempi fra Italia e Spagna (e oltre) (p. 63-76). Milano : LED.

Bressanini D., Toniato S. (2011). I giochi matematici di Frà Luca Pacioli. Trucchi, enigmi e passatempi di fine Quattrocento. Bari : Dedalo.

Baldasso R. (2010). Portrait of L. P. and disciple, a new mathematical look. The Art Bulletin, 92, p. 83-102.

Martelli M. (2010). Pacioli fra arte e geometria. Sansepolcro : Centro studi Mario Pancrazi.

Ulivi E. (2009). Documenti inediti su Luca Pacioli, Piero della Francesca e Leonardo da Vinci, con alcuni autografi. Bollettino di storia delle scienze matematiche, 29(1), p. 1-144.

Ciocci A. (2009). Luca Pacioli tra Piero della Francesca e Leonardo. Sansepolcro: Aboca museum.

Ghattas R., Ughi E. (2008). La matematica a Perugia, Scienza e scienziati a Perugia. Le collezioni scientifiche dell’Università degli Studi di Perugia. Milano: Skira.

(2007). Gli scacchi di Luca Pacioli: Evoluzione rinascimentale di un gioco matematico (Catalogo della mostra, Firenze, Gabinetto Disegni e Stampe della Galleria degli Uffizi, 23 giugno-2 settembre 2007), Sansepolcro: Aboca Museum.

Contin D. (2007). Gli scacchi di Luca Pacioli. Nuova informazione bibliografica, (3), p. 547-550.

Tavoni M. G. (2006). Sommario e indici nel fascicolo del De arithmetica e geometria di Luca Pacioli fra Quattro e Cinquecento. Rara volumina, 13(1), p. 5-13.

Ciocci A. (2003). Luca Pacioli e la matematizzazione del sapere nel Rinascimento. Bari: Cacucci.

Baader H. (2003). Das fünfte Element oder Malerei als achte Kunst das Porträt des Mathematikers Fra Luca Pacioli. In V. von Rosen (Ed.). Der stumme Diskurs der Bilder. Reflexionsformen des Ästhetischen in der Kunst der Frühen Neuzeit (p. 177-203). München ; Berlin : Deutscher Kunstverlag.

URILAND.IT Delle forze numerali cioe de Arithmetica. (2003). Consultabile sul sito web http://www.uriland.it/matematica/DeViribus/indice1.html

Tomlow J. (2000). Eine physikalische Interpretation des gläseren Objekts auf dem Portrait L. Paciolis von Jacopo de’ Barbari (1495). Architectura, 30, p. 211-213.

Mattarelli B. (1999). Léonard de Vinci et Luca Pacioli dans la Sainte Anne (1510). In De Poli L. Mnémosyne (p. 111-136). Bergamo : University press.

Giusti E. (Ed.) (1998). Luca Pacioli e la matematica del Rinascimento : atti del Convegno internazionale di studi, Sansepolcro 13-16 aprile 1994. Città di Castello: Petruzzi.

Nakamura T. (1997). Leonardo e Luca Pacioli: lo studio della proporzione. Bijutsushigaku, 19, p. 83-87.

Field J. V. (1997). Rediscovering the Archimedean polyhedra: Piero della Francesca, Luca Pacioli, Leonardo da Vinci, Albrecht Dürer, Daniele Barbaro and Johannes Kepler. Archive for history of exact sciences, 50, p. 241-289.

Mattesini E. (1996). Luca Pacioli e l’uso del volgare. Studi linguistici italiani, 22, p. 145-180.

Daly Davis M. (1996). Luca Pacioli, Piero della Francesca, Leonardo da Vinci: tra “proporzionalità” e “prospettiva” nella «Divina proporzione». In M. Dalai Emiliani, V. Curzi (Eds.). Piero della Francesca tra arte e scienza. Atti del convegno internazionale di studi, Arezzo, 8-11 ottobre 1992, Sansepolcro, 12 ottobre 1992 (p. 355-362). Venezia: Marsilio.

Ricci L. (1994). Il lessico matematico della «Summa» di Luca Pacioli. Studi di lessicografia italiana, 12, p. 5-71.

Giusti E., Maccagni C. (1994). Luca Pacioli e la matematica del Rinascimento (catalogo della mostra, Sansepolcro). Firenze: Giunti.

Pancrazi M. (1992). Luca Pacioli, la “Summa” e la matematica del ‘400. Sansepolcro: Arti Grafiche.

Picutti E. (1989). Sui plagi matematici di frate Luca Pacioli. Le scienze, p. 72-79.

Dalai Emiliani M. (1984). Figure rinascimentali dei poliedri platonici, qualche problema di storia e di autografia. In P. C. Marani (Ed.). Fra Rinascimento, Manierismo e realtà, scritti di Storia dell’arte in memoria di Anna Maria Brizio (p. 7-16). Firenze: Giunti Barbera.

Di Teodoro F. P., et al. (1981). Una ipotesi sui rapporti dimensionali del ponte a S. Trinita. Firenze: Giunti-Barbera.

Maccagni (1981). Le scienze nello Studio di Padova e nel Veneto. Storia della cultura veneta, III, Vicenza: N. Pozza.

Daly Davis M. (1977). Piero della Francesca’s mathematical treatises. The «Trattato d’abaco» and «Libellus de quinque corporibus regularibus». Ravenna.

Rackusin B. (1977). The architectural theory of Luca Pacioli: De divina proportione. Bibliothèque d’Humanisme et Renaissance, 39(3), p. 479-502.

Battisti B. (1974). Bramante, Piero e Pacioli ad Urbino. In Studi bramanteschi. Atti del congresso internazionale Milano, Urbino, Roma. Roma, p. 267-282.

North J. D. (1965). Apian and Pacioli’s polyhedra. Physis, 7, p. 211-214.

Nardi B. (1963). La scuola di Rialto e l’Umanesimo veneziano. In Branca V. Umanesimo europeo e umanesimo veneziano. Firenze: Sansoni.

Masotti Biggiogero G. (1960). Luca Pacioli e la sua Divina proportione. Rendiconti dell’Istituto lombardo, Accademia di scienze e lettere, classe di scienze, 94, p. 3-30.

Pedretti (1957). Il De viribus quantitatis di Luca Pacioli. Studi vinciani, p. 43-51.

Castiglione T. R. (1954). Un prezioso manoscritto del rinascimento in Svizzera. Luca Pacioli e Leonardo da Vinci a Ginevra. Cenobio, 3, p. 271-186.

Speziali P. (1953). Léonard de Vinci et la Divina proportione de Luca Pacioli. Bibliothèque d’Humanisme et Renaissance, 15, p. 295-305.

Ricci I. (1940). Fra Luca Pacioli. L’uomo e lo scienziato (con documenti inediti). Sansepolcro: Stab. Tip. Boncompagni.

BIOGRAPHY RESEARCH ACTIVITIES

RESEARCH ACTIVITIES PUBLICATIONS AND FINDINGS

PUBLICATIONS AND FINDINGS PLACES TO VISIT

PLACES TO VISIT