Itinerary edited by UNIVERSITY OF PERUGIA

The Studium in the Fourteenth Century

The Studium between the 15th and 18th Centuries

The University in the 19th Century

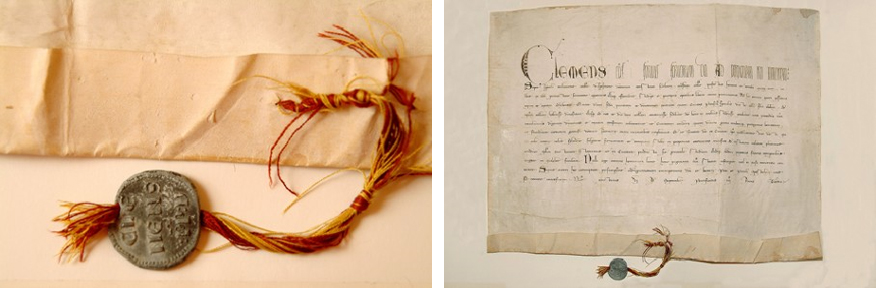

The City Council of Perugia, through a regulation under the Statute of 1285, agreed to promote the creation of a "Studium ut civica Perusii sapienti avaleate lucere et in ea Studium habeatur" ("a Studium so that the city of Perugia shines for its wisdom and that this should dwell within this Studium"). This type of Studium is defined as "unusual" because the awarded honours were only valid for the City of Perugia. The only thing that the Studium of Perugia was missing to become a “Studium Generale" was papal recognition, which arrived in 1308, on September 8th, with a Bull issued by Pope Clement V. In 1318, Pope John XXII bestowed the Studium of Perugia with the right to grant doctoral degrees in Civil and Canon Law, and in 1321 in Medicine and the Arts. Imperial recognition came in 1355, when on May 19th Charles IV awarded the city with a diploma that granted the title of “Studium Generale” in perpetuity. The history of the University can be told from different perspectives – chronological, legal, geopolitical - but for our purposes, that which traces the succession of scientific teachings and the evolution of university museums seems to be the most interesting, as it is a living witness to the circulation of culture and ideas.

During the fourteenth century there were two active Faculties at the Studium of Perugia: Law and General Arts. However, Medicine, Philosophy and Logic distinguished themselves almost immediately from the other Arts. The City Council granted those who attended the Studium, the "pupils", with the privilege of being able to create student organisations within the University, headed by a rector. Throughout the century, eminent professors were hired to teach in Perugia and the jurists included: Iacopo da Belviso; Cino dei Sinibuldi da Pistoia; Bartolo da Sassoferrato and Baldo degli Ubaldi, who for thirty years, from 1348, was a language assistant for the Studium’s university courses. One of the most illustrious doctors was Gentile da Foligno, who was struck down by the plague in 1348 and who remains one of the greatest scientists of the fourteenth century.

During the fourteenth century there were two active Faculties at the Studium of Perugia: Law and General Arts. However, Medicine, Philosophy and Logic distinguished themselves almost immediately from the other Arts. The City Council granted those who attended the Studium, the "pupils", with the privilege of being able to create student organisations within the University, headed by a rector. Throughout the century, eminent professors were hired to teach in Perugia and the jurists included: Iacopo da Belviso; Cino dei Sinibuldi da Pistoia; Bartolo da Sassoferrato and Baldo degli Ubaldi, who for thirty years, from 1348, was a language assistant for the Studium’s university courses. One of the most illustrious doctors was Gentile da Foligno, who was struck down by the plague in 1348 and who remains one of the greatest scientists of the fourteenth century.

The Popes, in their role as “reigning popes”, took the initiative to develop and manage the University of Perugia: in 1467, Pope Paul II ordered his governors to intervene in the management of the institution and this intrusion had profound repercussions on the Studium, which, deprived of its autonomy, plunged into a crisis that lasted throughout the 16th century. Nevertheless, new subjects were still introduced during this period: between 1525 and 1537 there were basic theory and practical lessons, among the first in Italy, and in 1580 the Chair of Anatomy and Surgery was established, held by Pietro Paolo Galera from the University of Padua. The University’s students included Castore Durante, one of the most famous botanists of the time, and Joannes Van Heeck, who graduated in Medicine in 1601 and who was one of the founders of the Accademia dei Lincei. In 1625, Pope Urban VIII provided for a radical reform of the Studium with the short act “Pro directione et gubernio Studii Perusini”, as well as considering the obligation for professors to have Perugian citizenship: the reform saved the University, but it led to it taking on, in the century of the scientific revolution, a far too local connotation. One of the most open professors at that time was Ludovico Pacini Viti, who steered his students towards Hippocrates’s empiricist approach and simplified therapies. The most famous Perugian scientists of this era were taught by him:  Filippo Belforti; Virgilio Cocchi; Prospero Mariotti and Alessandro Pascoli. In 1720, Filippo Belforti founded the University’s first botanical garden and in 1759 Luca Pellicciari began collecting physics laboratory equipment: this was the University’s very first museum collection. During the same years, Medicine and Botany were introduced at the Studium, taught by the most prepared Perugian intellectual of the eighteenth century: Annibale Mariotti, who during the Jacobin period also held the position of "Director of Studies", in order to allow him to implement the Jacobin reform of the University. In August 1799, the city capitulated in the face of pro-papal Austrian troops and proposals for modernising the University were momentarily set aside due to the first Restoration.

Filippo Belforti; Virgilio Cocchi; Prospero Mariotti and Alessandro Pascoli. In 1720, Filippo Belforti founded the University’s first botanical garden and in 1759 Luca Pellicciari began collecting physics laboratory equipment: this was the University’s very first museum collection. During the same years, Medicine and Botany were introduced at the Studium, taught by the most prepared Perugian intellectual of the eighteenth century: Annibale Mariotti, who during the Jacobin period also held the position of "Director of Studies", in order to allow him to implement the Jacobin reform of the University. In August 1799, the city capitulated in the face of pro-papal Austrian troops and proposals for modernising the University were momentarily set aside due to the first Restoration.

In 1809, a provisional plan for the chairs of artists was presented to the Napoleonic government, which included the establishment of several new chairs of Natural History, Chemistry, Veterinary Medicine and Agriculture. It also seemed like an opportune time because in Italy the Napoleonic period was seen as one of the most vital periods for the progress of sciences. In 1810, the Studium was allocated a new building, the Montemorcino convent, and among the University’s top priorities was the enrichment and ex-novo formation of studies and museum collections for teaching purposes.

The return of the papal government, with the second Restoration, blocked the application of the Napoleonic reforms, but the professors and students had already been able to benefit from the advances of French and European science. At the beginning of 1850, with the end of the Roman Republic, the technical staff at the museums which had adhered to the Republic were removed by the papal government, including the naturalist and explorer Orazio Antinori, initiator of the University’s zoological collections. It was pretty clear, also at a political level, how closely connected the modernisation of the disciplines was with the question of national Unity.

In 1860, Savoy troops entered the city and immediately started to modernise teaching methods, hiring young positivistic professors who were well disposed towards experimental science and the most groundbreaking theory of that era: Darwin's theory of evolution. The most important professors during the post-unification period included: physicist and geologist Enrico dal Pozzo Di Mombello, physiologist Luigi Severini, agronomist Raffaele Antinori, naturalist Andrea Batelli and veterinarian Eugenio Aruch, who were committed to improving the existing museums and to creating new ones.

At the end of the nineteenth century, the University building was largely occupied by a well-stocked library and museums dedicated to the following scientific disciplines: Physics, Mineralogy, Earth sciences, Human Anatomy, Botany, Zoology and Comparative Anatomy. These were flanked by the Medieval History museum, the numismatic collection, the Orazio Antinori Ethnological collection, the Guardabassi Art Gallery and the Etruscan museum established by the University's archaeology professors, Giambattista Vermiglioli and Giancarlo Conestabile della Staffa. In 1896, the San Pietro Agricultural High School was inaugurated by Eugenio Faina, which had more museums and libraries and filled the gap of agriculture not being offered as a university subject.

Over the course of the century, the university steadily expanded its subjects and faculties: in 1900 there were 19 full and associate professors, in 1950 there were 49, and by the end of the century there were over 1100. The first half of the century saw many changes in the structure of the science faculties: in 1924 the Veterinary School became a Faculty under the guidance of Giovanni Battista Caradonna and in the same year Raffaello Silvestrini organised the new Monteluce hospital, where the Medical Faculty’s clinics and new schools were located. In 1936, a Royal Decree established the Faculty of Pharmacy and in 1937 the San Pietro Agricultural High School became part of the University as the Faculty of Agriculture. During the Fascist era, however, there was less interest in science museums and after World War II the old collections formed under the auspicious influence of positivism were put aside to make room for new chairs. When in the mid-90s the University Centre for Scientific Museums was established, it was hard to even imagine what was left of the museum heritage, but thanks to many initiatives, including an exhibition for the University’s seventh centenary in 2008, it was possible to see the extraordinary historical value of what remained. Today the museum heritage is divided into two centres: San Pietro, which includes the Botanical Garden and the Medieval Garden, and Casalina, which includes the Natural History Gallery, the History of Agriculture Laboratory, the Mathematics Gallery and the Anatomy museum, which is currently being set up. In the city centre, the University’s Plaster Cast Gallery has also been conserved.

With its strong secular tradition, the University is the ideal place for young people who choose to do their university studies at one of its numerous education support structures in Perugia, Assisi, Foligno, Narni or on the Campus in Terni. Today there are sixteen active departments: Chemistry, Biology and Biotechnology, Economics; Philosophy, Social, Human and Learning Sciences; Physics and Geology; Jurisprudence; Engineering; Civil and Environmental Engineering; Languages, Literature and Ancient and Modern Civilization; Mathematics and Computer Science; Experimental Medicine; Veterinary Medicine; Agricultural, Food and Environmental Sciences; Surgical and Biomedical Sciences; Pharmaceutical Sciences; Political Sciences.

HISTORY  RESEARCH ACTIVITIES

RESEARCH ACTIVITIES DIDACTIC HISTORY

DIDACTIC HISTORY GREAT EVENT

GREAT EVENT PLACES TO VISIT

PLACES TO VISIT