Itinerary edited by SAPIENZA UNIVERSITY OF ROME

To the side:

View of the Roman Forum by Piranesi

Buildings, monuments, street decors and roads say a lot about the geology of the territory where cities are located. Each city has its own characteristic colours, those of materials used in construction and cladding. Obviously this applies above all to our cities and towns which boast a millennial history: since the dawn of time, material has been sourced as close as possible to areas of use, for convenience, out of choice or necessity. OnceRome, as a rich capital of an immense empire, was characterised by the most valuable "coloured marbles". Later, Popes and noblemen used the same marbles recovered from the Imperial Roman constructions, for the embellishment of churches and palaces. The city's roads and alleys remain nonetheless characterised by the warm tones of Roman plasters, together withthe white colour of thetravertine stone, the yellow and grey of tufa and the red of bricks.

Buildings, monuments, street decors and roads say a lot about the geology of the territory where cities are located. Each city has its own characteristic colours, those of materials used in construction and cladding. Obviously this applies above all to our cities and towns which boast a millennial history: since the dawn of time, material has been sourced as close as possible to areas of use, for convenience, out of choice or necessity. OnceRome, as a rich capital of an immense empire, was characterised by the most valuable "coloured marbles". Later, Popes and noblemen used the same marbles recovered from the Imperial Roman constructions, for the embellishment of churches and palaces. The city's roads and alleys remain nonetheless characterised by the warm tones of Roman plasters, together withthe white colour of thetravertine stone, the yellow and grey of tufa and the red of bricks.

The "stones of Rome" tell about the city and its surrounding areas a story which covers, by leaps and bounds, a time frame of approximately 4 million years and takes start before the foundation of the city itself.

We have divided this long history into some phases:

I - Before Rome: the Pliocene sea

I - Before Rome: the Pliocene sea

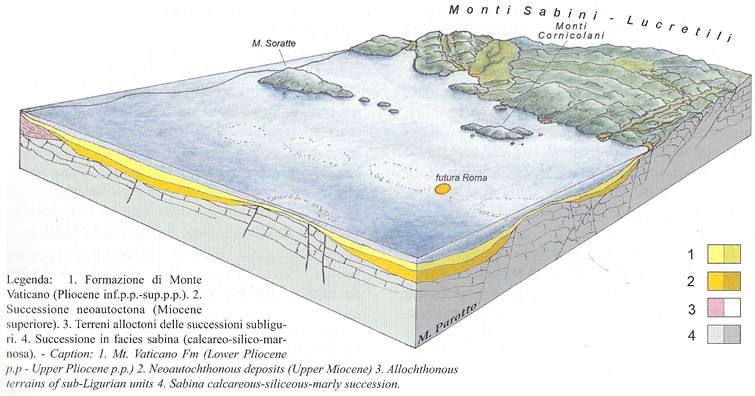

Approximately 3.5 million years ago (during the Pliocene), the today's Tyrrhenian coastal plain, where the city will develop, was a widerelatively-deep sea, from which a few islands emerged, such as Soratte, the Cornicolani M.ts or the Circeo Promontory. The coastline ran along the edge of the peaks of what are now Mounts Sabini, Lucretili and Prenestini.

Prevalently fine sediments settled at the bottom of this sea to form the “Monte Vaticano” Formation, commonly known as “Argille azzurre”. Until recent times, these clays were used to construct bricks which were widely used in the city of Rome. The most important furnaces, where generations of workers (“fornaciari”) were employed, were located in the Valle Aurelia; their remains are still visible, as veritable industrial monuments.

In the Early Pleistocene (approximately 1.6 - 1.5 million years ago), the "Monte Mario" Formation deposited over the “Argille azzurre” in a sea which by now had become much shallower. The base of this Formationis formed by sands containing rich faunas of molluscs including Arctica islandica, a cold sea bivalve which migrated to our regions during the glacial period.

In the Early Pleistocene (approximately 1.6 - 1.5 million years ago), the "Monte Mario" Formation deposited over the “Argille azzurre” in a sea which by now had become much shallower. The base of this Formationis formed by sands containing rich faunas of molluscs including Arctica islandica, a cold sea bivalve which migrated to our regions during the glacial period.

II -

Before Rome: volcanic landscapes

II -

Before Rome: volcanic landscapes

During the last 600,000 years, due to the progressive retreat of the coastline towards its current position, the future "Campagna romana" was represented by a flat or hilly landscape, dominated by a few volcanoes. Let us imagine this scenario by looking at the painting by Johann Jakob Frey from 1858, which depicts Rome and the Tevere valley with the Volcano of the Alban Hills in the background: the city and "human" presence blend somewhat seamlessly with the natural landscape.

During the last 600,000 years, due to the progressive retreat of the coastline towards its current position, the future "Campagna romana" was represented by a flat or hilly landscape, dominated by a few volcanoes. Let us imagine this scenario by looking at the painting by Johann Jakob Frey from 1858, which depicts Rome and the Tevere valley with the Volcano of the Alban Hills in the background: the city and "human" presence blend somewhat seamlessly with the natural landscape.

Volcanoes, owing to their magic fascination of fire-breathing mountains and their soil fertility, have always attracted man's attention. Frequently they have forced man into a dangerous cohabitation which has inspired researchers to interpret nature and origin of these mountains.

The figure on the left represents how Athanasius Kircher, a Jesuit and important exponent of 17th century naturalistic culture, imagined fire emerging from the depths of the Earth, feeding volcanoes through a series of chambers, increasingly close to the surface, in his “Mundus subterraneus” (1664).

The Geology Museum as well as few other Museums at La Sapienza University of Rome house items from the ancient Kircher Museum.

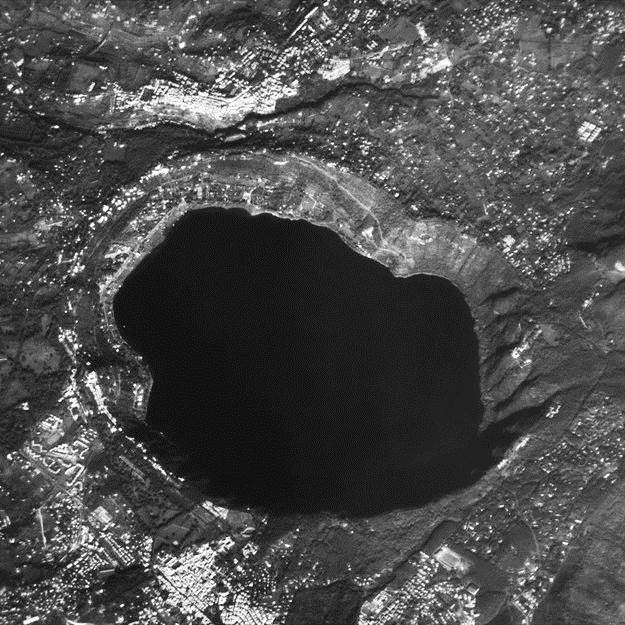

The Alban Hills, with Mount Cavo and the “Campi di Annibale” rich in woods and springs, legends, fruitful soils, wines and taverns (commonly known as “fraschette") are the remains of a large volcano.

Rome was born where the pyroclastic deposits and lavas of the Alban Hill volcanoes to the south east, converge with those of the Sabatini volcanic complex to the north-west.

Much of this volcanic material constituted one of the main material sources for the construction of palaces, temples and roads in ancient Roman times.

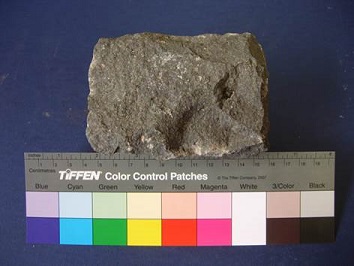

The most extensively used materials include the "Tufo giallo della via Tiberina" (an ignimbrite from approximately 550,000 years ago) and the "Tufo rosso a scorie nere" (an ignimbrite dating back approximately 430,000 years), both from the Sabatini volcanoes.

On the contrary from the Alban Hills volcanic district come other commonly used material such as the "Pozzolane nere" (a pyroclastic flow dating back to approximately 407,000 years ago), the "Tufo lionato", (a pyroclastic flow whose age varies from 338,000 and 357,000 years) and the "Capo di Bove" lava (approximately 280,000 years ago).

The last, violent explosions of the Alban Hills date back to approximately 40,000 years ago and led to the formation of the Albano, Nemi and Ariccia lakes (renowned outing destinations for ancient and modern Rome inhabitants). This last explosive phase gave origin to a pyroclastic deposit known as "Peperinoalbano" (a freatomagmatic ignimbrite, approximately 36,000 years ago). Its name was inspired by its characteristic and numerous black crystals (pyroxene and biotite), which look like pepper corns.

III - The Seven Kings and Republican Rome

III - The Seven Kings and Republican Rome

The long history of Rome began on 21st April 753 BC: immediately the city felt the need to surround itself with increasingly robust defensive walls. The ramparts and massive walls from the 6th century BC of King Tarquinius Priscus and ServiusTullius (from the 4th century BC) were overshadowed by the imposing "mura serviane", these city walls, approximately 11 km in length, were constructed with blocks of "Tufo giallo della Via Tibertina" (from the Sabatini volcanic complex)

Innumerable sections of these walls are spread throughout the heart of Rome, including a long stretch visible in the vicinity of Stazione Termini, as well as others near the Quirinale Palace on Largo Magnanapoli.

Over time increasingly magnificent buildings and temples to the Gods were erected and bridges were constructed with blocks of “Peperino albano”, “Tufo lionato” and “Tufo rosso a scorie nere”.

The sacred area in Torre Argentina contains numerous temples from the 3rd and 2nd centuries BC; one of the oldest sacrificial areas is made of "Peperino albano", whereas the more recent group of columns arranged in a semicircle is made of "Tufo lionato".

In the ancient Pons Aniensis (Ponte Salario), the remains of a Roman structure, probably dating back to the republican age, are still visible, including two side arches, with paraments made of blocks of “Tufo rosso a scorie nere”

Over time an increasingly dense network of roads linked the city to its provinces; large paving blocks are still recognisable in numerous places on the Italian peninsula.

Along the ancient Via Appia, one of the most renowned consular roads, sections of the paving with classic "basoli" , consisting of large square black blocks of lava from the Alban Hills volcano, arestill clearly visible. The same material was also used in the construction of the most famous “sanpietrini”. This material mostly derived from the quarries opened in the Capo di Bove lava flow, which from the Alban Hills volcano reaches the city of Rome.

IV - Imperial Rome

IV - Imperial Rome

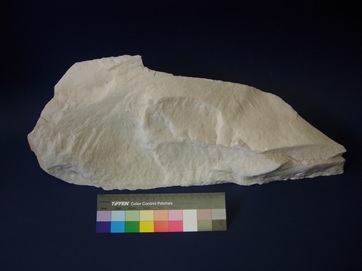

In order to make the City even more magnificent and no longer satisfied with material from nearby territories, the Roman Emperors, transformed Rome into a city of arrival for splendid "marbles" used to erect arches, temples, columns and for decorations. “Marmor lunensis”, the purest of all Carrara marbles, was used in rich and detailed decorations of commemorative monuments.

The bas-reliefs of the Trajan Column and decorations of the Arch of Constantine are both in "marmor lunensis".

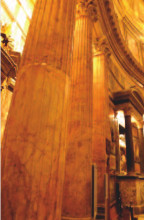

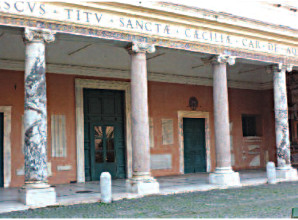

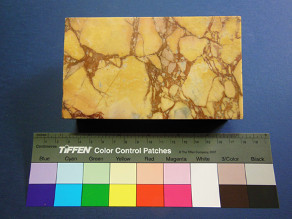

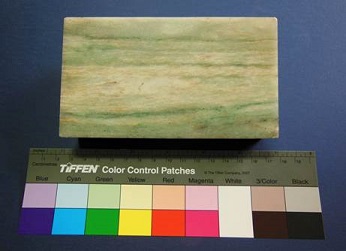

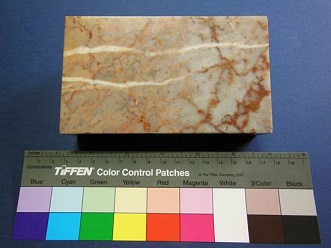

Splendid examples of most Roman "coloured marbles" in the city are still visible and have also been re-used in successive periods, as is the case of the so-called "Marmo africano" (here below, to the left). There are also examples of beautiful "Giallo antico" (or “Numidia marble” - here below, on the right), used for the large columns inside the Pantheon.

Splendid examples of most Roman "coloured marbles" in the city are still visible and have also been re-used in successive periods, as is the case of the so-called "Marmo africano" (here below, to the left). There are also examples of beautiful "Giallo antico" (or “Numidia marble” - here below, on the right), used for the large columns inside the Pantheon.

The “Granito rosso di Assuan” was also popular among Romans, and even before it was used by the Egyptians from the first dynasty. This material became renowned due to its use in the creation of obelisks. The Lateran obelisk which dominates piazza S. Giovanni in Laterano, was moved to Rome by the Emperor Constantine.

The small obelisk (here on the far right, with the Pantheon dome in the background),that was positioned on an elephant-shaped base by Bernini, is also made of the same material.

Other materials used frequently by the Romans include Pozzolans, both as aggregates for the preparation of mortars, and to "lighten" roof structures, such as the large dome of the Pantheon. Part of the Pozzolans came from the “Pozzolane nere” Unit of the Alban volcanic district.

V - Medieval Rome and the Cosmati

V - Medieval Rome and the Cosmati

The most resistant and long-lasting "marbles" were used for splendid and multicoloured inlay flooring, both in buildings during Roman times ("opus sectile") and in Romanesque Christian basilicas, until the 15th century. The Cosmati art refers to the name of famous marble workers in Rome from different generations and families. This style, especially flourished during the 12th and 13th centuries, typically reused Ancient Roman marble remains to create highly evocative geometric compositions in church pavements and cloisters.

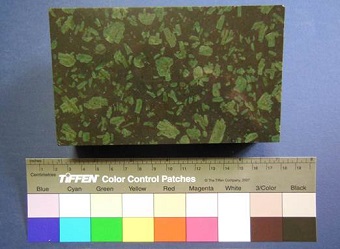

In particular the “Porfido rosso and the “Porfido verde antico” werefrequently used as, for example, in the "rotae" of pavement of the of S. Alessio church (the “rotae” were cross sections of Roman columns)

VI - Papal Rome

VI - Papal Rome

The ruins of ancient Rome continued to be used as an immense and extremely rich quarry, from which for centuries marble workers extracted colourful marbles to decorate churches and monuments, also erected in celebration of the magnificence of papal Rome.

The marble known as “Portasanta” (“Chio Marble” of the Romans) is perhaps the greatest symbol of the papal Rome. Indeed this rock was used to clad the jambs of the Porta Santa (which gave rise to this marble's name), present in all the four greatest basilicas of Rome.

During this period also the Cipollino marble was widely appreciated. Numerous Roman columns, re-used in the city's churches, are made of this stone..

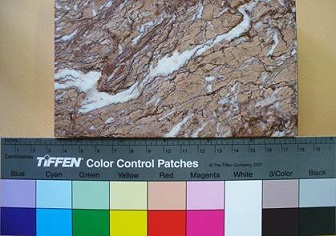

From the 17th century on, a depletion of the reserve of re-usable ancient Roman material led to the sourcing and exploitation of "marbles" from modern quarries. One example is the "Cottanello marble", which although already extracted in Roman time, came to be extensively used for the interiors of numerous baroque churches in Rome. Large columns inside St. Peter's Basilica are made from this rock.

VII - Rome Capital of the Kingdom of Italy

VII - Rome Capital of the Kingdom of Italy

After the 20th September 1870, when Italian troops entered Rome through“PortaPia”, Rome became the capital of the Kingdom of Italy. The city underwent a renewed process of urban development and there was also an increase in the use of rocks which did not belong to local tradition.

The parapets of the large walls constructed to channel and control the Tevereriver are made from “Granito di Baveno”, a rock quarried in Piedmont region (western shores of Lake Maggiore).

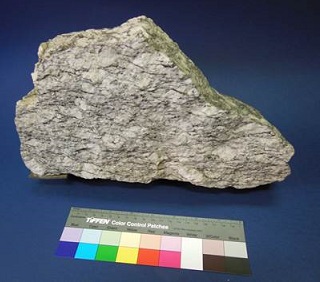

Slabs of “Gneiss occhiadino”, from the Alps, were also used as pavement blocksin Via del Corso.

For the large and famous monument to Victor Emmanuel II, the “marble” known as "Botticino", an extremely white rock from the Brescia area in Lombardy region,was extensively used.

VIII - The “Ventennio” - The Fascist Period

VIII - The “Ventennio” - The Fascist Period

During the fascist period Rome underwent another "architectonic revolution", characterised by extensive demolition and great architectonic works.

Travertine (Lapis tiburtinus of Tivoli), also called "the Stone of the Empire", became one of the most extensively used materials. Owing to its resistance and the fact that it is easy to process, its homogeneous brightness, its autarchic cheapness and its vicinity to the capital,the travertinefitted well to the essential geometry of the architecture of this age.

Students in Rome are undoubtedly familiar with the University City, designed by the architect Marcello Piacentini and officially opened in 1935. The cladding of the monumental entrance and the buildings on piazza della Minerva, dominated by the Rectorate's building, are all made of travertine. The Geology and Mineralogy building, designed by Giovanni Michelucci and home to the Museum of Geology, are also covered with travertine.