The University of Modena and Reggio Emilia owns a collection of metrological instruments related to the attempts occurred between the end of the eighteenth and begin of the nineteenth century, to reorder and control on the local communities and on their old metrological prerogatives that led to the realization in the second half of the nineteenth century of the Metrology Laboratory. It was held in the rooms adjacent to the Astronomic Observatory placed on the Eastern Tower of the Ducal Palace.

In Modena, the public control on weights and measures was exercised by the office of “Buona Opinione” (Good Opinion), whose existence is documented since the Statutes of 1327.

In the Statutes of the Community of Modena of 1547, the norms concerning the Office of Good Opinion did not undergo significant changes compared to the previous years; the Statutes represented the fundamental instrument of city government, and thanks to them the Community enjoyed of a big autonomy towards the Ducal power.

The 5th book of the Statutes disciplined the administration of Vettovaglie (Victuals). The Judges of the Victuals, employed by the Ducal Chamber, had the control on weights and measures. They were chosen between the Conservatori della Comunità (Custodians of the Community) that submitted the nomination to the Este Duke, who took the final decisions in case of controversies. This right was often exercised in favour of sovereignty and caused conflicts between the interests of the ruling class of the Community and the ducal government.

In January 1607, the complex topic of public control of the measures was further defined by the approval, by the Counsel of Custodians of Modena, of the Chapters that specified the procedures of nomination of the Good Opinion Officer and his functions. Among his duties there were the custody of samples of weights and measures and their restitution, at the expiration of the mandate. Some examples of these models are preserved in the Civic Museum of Art of Modena. The Chapters remained in force until 1806.

The attempts to unification of weights and measures in the Eighteenth century

The attempts to unification of weights and measures in the Eighteenth century

In the second half of the Eighteenth century, the new cultural climate created by the influence of the transalpine Enlightenment, along with the period of peace and political stability, emphasized the urgency of a general reform of financial and politic structures of the State. In the 1780s, new demands for the measuring of the territory and for the economic activities, functional to the State Administration, made the interest in the reform and unification of systems of measures more pressing.

Following the debate, originated in scientific and cultural circles, in 1781 in Milan started the unification of weights and measures, followed in 1782 by the Grand Duchy of Tuscany. In Modena, despite the solicitations of Giovanni Battista Venturi (1746-1822), physicist and moving force of the scientific circles of Modena, the topic was confined to academic environments.

This important reform would have generated important economic implications; a unitary system would have favoured the promotion of internal and external trade which at that time was slowed by a metrological multiplicity, avoiding frauds originated by long and difficult calculations of comparison.

In 1787 Venturi, who was already the holder of the chair of Geometry, Philosophical institutions and Physics at the University of Modena, was appointed Ducal Mathematician and received the duty of supervise the affairs relating to currencies, measures, and weights of the State.

In vain, attempts were made to unify the weights and measures in the Este State, also because of the resistance of local communities to the Este authorities, which was increasingly trying to take back the authority of the Good Opinion Office, reducing its prerogatives and incomes.

Between 1797 and 1798, In Milan Venturi took part to the works of the newborn Commission of the Cisalpine Republic, entrusted to follow the regulations on trade, finance, measures and coins. In this field, he made some proposals, but without success.

Basing on the model of the young French Republic, Venturi, following the choice of decimal subdivision, proposed to adopt the “cisalpine arm” (corresponding to half meter) for the measures of length and the “gram of France” for mass measures, keeping, as much as possible, the ancient denominations and allowing the private the use of current measures in their transactions.

He realized conversion tables using physics instruments and standard measurements of the Physical Theater of the University of Modena, of which, in the meanwhile, he had been appointed Director.

Among these instruments, now owned by the University Museums, there was the precision balance that Venturi gave instruction to realize to the monk and engineer Agostino Arleri (1741-1821) for the Physical Theater and which was used to compare the pounds of the different parts of the Cisalpine Republic with the samples of the small pound of Milan and of the gram of Paris.

Other instruments that Venturi gave instructions to purchase for the experiments in the Physical Theater and nowadays present in the University Museums are the Meurand’s standard fathom, a Pound of Paris and a standard meter made by Etienne Lenoir.

The fathom is the old French sample of length that, according to tradition, was based on the height of Charlemagne. It was also called "of Peru" because between 1736 and 1744, it was used to measure the terrestrial meridian to the equator in Peru.

In 1766, the king Luis XV admitted this archetype as national sample for the length measures. The Peru fathom was used to fix the value of the provisional sample (1795) and of the final sample (1799) of the meter, in other words 10.000.000th part of a quarter of terrestrial meridian.

Since 1786, Giovanni Battista Venturi asked for the purchase of a fathom for the experiments in Physical Theater so that he could rely on the precision of the French archetypes. But only in 1789, due to the financial burdens that this purchase created, he successed to receive from Paris in Modena the fathom realized by the mechanic Meurand.

The director of the Paris Observatory Joseph-Jerome de Lalande (1732-1807), following a specific request of Venturi, did personally the comparison between the Meurand fathom and the one of the France Academy and took care about the delivery to the Physical Theater.

Also the pound or Mark of Paris, compared in 1767 with the archetype realized by the Paris Mint superintendent Tillet and lodged by the French mint, was one of the purchase that in 1789 Venturi proposed for the Physical Theater and it was used to fill the conversion tables among the measures of the Cisalpine Republic and the metric measures in 1798.

In 1797 Venturi bought the Lenoir standard meter in Paris and it was also used in Milan by the illustrious professor for the compilation of the conversion tables; Lenoir (1744-1832) was, in fact, the first to manufacture samples of measurements according to the French metric decimal system.

Among the instruments that Venturi brought with him to Milan and today present in the University Museum there were even a half fathom divided into feet and inches and an iron ruler, both kept in a walnut case. These two instruments, present in the inventories of the Physical Theater without the date of entry, were probably acquired between 1789 and 1792.

Proof of the experiments of Chemistry and Physics in the Physical Theater, there is also the presence between the objects of the museum’s collection, of a box of weights coming from the end of nineteenth century with the ounce of Paris, of Bologna and of Modena and their submultiples. Venturi remembered that the physicists always used the measure of Paris in their experiments.

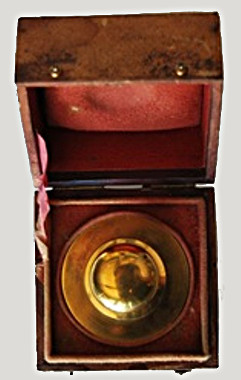

Among the items kept in the collections of University Museums, there is also a stack of weights of 4 Troy ounces mass with bronze glass shape, stacked one inside each other; these weights were also known with the name of "weights in Nuremberg’s style", the city that held a kind of monopoly in Europe in their manufacture. Venturi, during is charge of director of the Physical Theatre, bought for his experiments the best samples of measure existing in Europe and, probably, this object was bought in this contest.

The French model, between revolution and restoration

The French model, between revolution and restoration

The law of the 27th of October 1803 introduced finally the French metric system in the Italian Republic. The law permitted not only the promiscuous use between the old and the new measures, but also to maintain the old denominations for the new measures, allowing in this way to the population to get used gradually to the new deal.

Despite the publication of the conversion tables, any precise date had been established for the entering into force of the new system, which was postponed both because of organizing difficulties in the manufactoring of the samples to give to the Community, and of the absence of a law that clearly gave to the administration of the State the right of stamp on weights and measures.

Two instruments today present in the collection of the University Museums belong to this period: the iron standard meter with its walnut case and a box of weights with metric pounds.

The standard meter, divided in decimeters and centimeters and the last decimeter also in millimeters, has two vertical external projections. It is a tongue and groove system, in which the official unit of measure was the one that perfectly fitted between the vertical projections.

This kind of model was typical of the ancient French measure instruments, which shortly after was adopted also in the Kingdom of Italy, when the samples of standard measures were realized to be delivered in the departments of the Kingdom.

The box of weights is composed of 24 brass metric weights of cylindrical shape with button, on each weight there is indicated its mass. Even though the French metric system had been introduced, to ease the adoption it was permitted to give to the new measures, as said above, the old denominations, reason why on each weight there is printed a wording in pounds, ounces, grosses, etc instead of kilogram, hectograms, decagrams and so on.

In the meanwhile, in Modena, the government relieved the Judged of Victuals of the verification and stamping of weights, measures and balances. This procedure occured every six months and concerned the instruments of all the people who sold publically with weight and measure the merchandise. The intent was to relieve the Office of Good Opinion of its power.

The Modenese Community's resistance lasted for a handful of years, till when in 1811, the law on the activation of new weights and new measurements was promulgated. It was based on the decimal metric system and on the verification of the marking, which was accomplished by verifiers appointed by the Minister of Finance.

After the Restoration of 1814, and the assignment to Francis IV of Austria Este of the Duchy of Modena, it witnessed a rather strange situation. Nobody thought to completely delete the weights and measures of the Revolution, it was promulgated a law that simply froze the situation present in that moment. In the fact, the metric measures lived together with the multitude of the local measures and the theme of metrological unification was set aside.

In 1846 in Piedmont, the idea of adopting the French metric system was resumed and weights and measures samples were ordered in Paris.

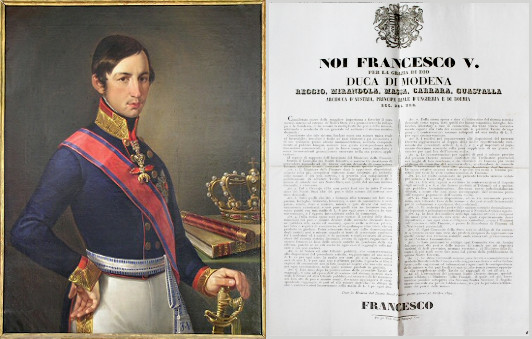

Some years later, also Francis V Archduke of Austria Este decided with an Edict issued on the 17th of October 1849, that starting from 1852 in the Este Dukedom the new metric decimal system and a new regulation for the verification would be adopted, so to standardize the measures which were still different from a place to another.

The reform was originated from the will of promoting trade development with other Italian states, particularly with the French-Piedmont axis, and with Austria, where the adoption of the decimal metric system was imminent.

A Special Commission, instructed by the Finance Ministry, had to carry out the tasks established by the decree of 1849: fill the regulation concerning the manufacturing of weights and measures, fill the conversion tables and take care about the realization of the samples. These operations needed comparisons with the archetypes of meter and kilogram created in France.

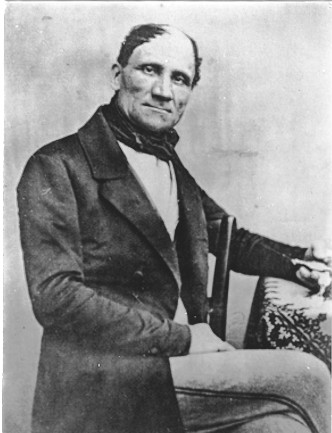

With a chirography dated 27 October 1849, Francis V appointed the Special Commission on weights and measures chaired by Stefano Marianini (1790-1866), president of the Science Society. Since from August, Marianini proposed to the Finance Minister, Ferdinando Tarabini, to instruct Giuseppe Bianchi (1791-1866), tutor of Francis V and director of the Astronomic Observatory, to go to Paris to purchase the instruments.

Bianchi, on suggestion of Marianini, wrote to the known French physicist Jean-Baptiste Biot (1774-1862) to ask for advice about the matter.

Thanks to the precious advice of Jean-Baptiste Biot, the Este government could address its resources towards more suitable French archetypes and instrumentations.

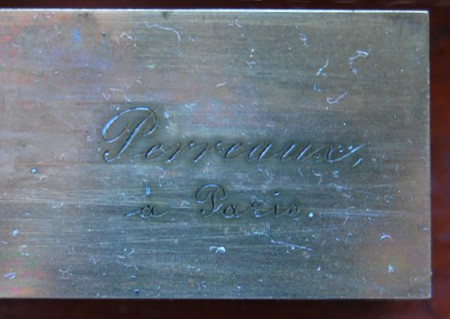

Biot advised not only the purchase of platinum archetypes instead of the ones made of brass; he also proposed the purchase of instruments for their manufacturing and duplication, proposing Guillaume Perreaux (1816-1889) for the manufacturing of the prototypes of the meter, the comparator and of the machine to divide in a straight line, and Louis-Joseph Deleuil (1795-1862) for the manufacturing of the kilogram and precision scales prototypes.

In August 1850, in the presence of Giuseppe Bianchi and under the guidance of Deleuil, Perreaux, Biot and Regnault (1810-1878), physicist and teacher at the College of France, began in Paris the first comparisons of the archetypes of meters and kilograms, addressed to the Duchy of Modena, with the French ones.

Today, these instruments are part of the collection of University Museums of Modena.

In the manufacturing of the comparator used to compare the different standard measurements of length, the Perreaux added compared to the model of the precise comparator of the Paris Astronomic Observatory, the possibility to move the front microscopes perpendicularly to the motion of the frame. The instrument, which today is part of the collection of the Astronomical and Geophysical Museum, is therefore an improvement than the previous model.

The Perreaux standard meter n. 2, now at the University Museum of Natural History and of Scientific Experimentation, was firstly compared with the platinum sample of the Bureau des longitudes of Paris, resulting 0.01333 millimeters longer than the French sample, later, having regard for the different coefficient of thermal expansion of brass and platinum, it was preferred to compare the Perreaux meter with a sample of the same material.

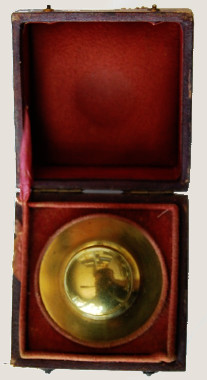

In the same museum, can be also observed the kilogram sample n. 2 manufactured by Deleuil. In his laboratory, he compared the brass kilogram sample deposited by the French Ministry of the Interior with the prototypes realized for Modena; the one of Modena resulted ¾ of milligram heavier. Later, Deleuil compared the brass kilogram of the French Ministry of the Interior with the platinum kilogram of the Paris Astronomic Observatory, noting a sensible difference between them. The difference of materials among two Paris samples and moreover the lack of exact data on physical elements of gas in the moment of the fixing of the mass of the platinum kilogram of the Observatory, persuaded to consider as right the brass sample of French Ministry of the Interior. The Modena samples didn’t receive any modification, since these ones were considered more similar than the platinum ones of the Observatory and a further change would have probably created some difference in the inverse sense.

In December 1850, once that the comparisons between the French samples and the Modena Archetypes were ended, the scientific instruments were sent to an apartment of the Ducal Palace (adjacent to the Astronomic Observatory) which was transformed in metrological laboratory; here Bianchi and Marianini checked for a last time the comparisons.

In January 1851, there was the official delivery to the Secret Archive of the meter numbered 1 and of the kilogram I, to the Finance Minister of the meter numbered 2 and kilogram II, while the meter numbered 3, the kilogram 0 and the machines, among those the Perreaux comparator and the machine to divide the straight line remained in the Astronomic Observatory.

In February 1851, Cesare Zoboli, already officer in the mechanic laboratory of the Observatory, was instructed to supervise “the use of the archetypes and machines already arrived from Paris”.

The work of the Commission wasn’t without obstacles. The Tarabini minister, in the fact, pushed so that the conversion tables were ended within the terms fixed by the measures of 1849.

Marianini in a letter dated October the 7th, 1851 to the Ministry of Finance gave the Regulation of metric measures conditions, but at the same time announced that the Conversion tables weren’t completed yet.

The greatest difficulties faced by the Commission were the poor collaboration of the local communities which, despite the ministerial circular sent to the Communities on January the 12th, 1850, were late to send the measurement samples and the news related to them, adopting the most varied motivations.

To these administrative difficulties were added the inadequacy of the premises used for the works both of the Commission and of the Metrologic Laboratory.

These inconveniences extremely prolonged the time of coming into force of the new system of measures, so that the Commission considered appropriate to postpone it on the 1st January 1853 as compared to what was laid down in the Decree of 1849, which set the deadline on the 1st January 1852.

It was not easy to instruct communities on new measures and weights; many communities were not even equipped with specimens, and there were doubts about the presence of workshops and architects capable of producing metric measurements.

Despite these downturns and pressures of the Minister who doubted of the work of the Commission, finally in August 1852 the hard work of measuring for the filling of the conversion tables ended up and the duke Francis V approved them together with the regulation of the 26th of August.

The Duke granted the faculty for a three-year period to use, in private transactions, the old units of measurement. After this period, private individuals would have to complement these with the corresponding decimal measures shown in the conversion tables.

But the situation was still uncertain and confused; the delegate of the Ministry of Intern noticed that it wasn’t clear if the samples of the new measures should have to be provided to the Community by the Ministry of the Finance or if the Community had to produce them by their own.

It was decided that the local administration should have the task to pay for the manufacturing of the sample to send, later, to the approval of the Commission. Some administrations shown interest in equipping of the samples realized eventually by Zoboli, some other communities called local artisans.

In the meanwhile, the works of the Commission and of the metrical laboratory proceeded slowly because of the difficulties faced in finding verifiers and skilled manufacturers for the new measures.

The stalemate that was created convinced the Ministry of Finance, with a notification of the 29th December 1855, to postpone further the entry into force of the decimal metric system at the 1st January 1857. In order to do not incur further delays and to provide as soon as possible the Communities of the sample series, the Ministry advocated the manufacture of the instruments.

The building of the Hannover stables was chosen as ideal location to held a metric workshop equipped with all the necessary facilities. The works of restorations and adaptation of the rooms started and Zoboli was entrusted as technical superintendent of the works. A real businessof industrial nature for the time, which would have to take the time necessary for the manufacturing of all series of samples for the duchy.

The laboratory opened in June 1856 and, even though some lack of staff and equipments, after few months it had already produced 72 meters for the Community and 14 series of brass samples of linear and mass measures created for the central and outlying offices of the administration of the State.

The liter sample and the half decaliter come from this period and are part of the collection of University Museums.

The liter sample, a brass cylinder, placed in its tin box, is without handles for gripping, unlike the designs in the Regulation around the conditions of the instruments for metric measurements of 1852; It was not even among the archetypes that Duke Francis V ordered in Paris, and for these reasons, it is possible to assume that this sample was manufactured in the metric laboratory.

The half decaliter was also manufactored in the metric laboratory between the end of 1857 and the beginning of 1858, the year in which the weights and measures Commission was dissolved. The punch on the upper edge shows an eagle with wrapped wings, the head looking links and surmounted by a crown and it is in that period that the Commission and the mechanic of workshop Zoboli proposed, as stamp to be attached to the samples of the series produced there, just an eagle surmounted by a crown.

Thanks to the competence of Marianini and Bianchi, the metrological laboratory earned a good reputation Italy wide, so that there it began to manufacture archetypes of meter and kilogram also for the Lombard-Venetian government, and this thanks to the instruments more at the state of art that they had as equipment.

Even though with thousand of difficulties, the work done from the illuminated and fervent minds of scientists and technicians of Modena played an important role in the development of the Italian metrology of which the University of Modena and Reggio Emilia stores the more precious witnesses.

The more representative instruments of the collection

The more representative instruments of the collection

Heads and sectors standard meter divided into decimeters and centimeters and the first decimeter also into millimeters. It permits to measure samples of length. In 1798, it was used in Milan to compile the conversion tables. Giuseppe Bianchi remembers that the Lenoir’s meter, was scrupulously compared with the arm of Modena by Giovanni Battista Venturi Abbot, who personally bought the Lenoir’s standard meter in 1797 . Also the Special Commission on weights and measures, established in December 1849, used this meter to work on the comparison of linear measures used by the Dukedom.

Comparator-microscope with molten iron base on which two iron sideways are placed. On these sideways there is a loom of the same material that has at the front two brass tube microscopes and vertical axis, equipped in the lower part with screws for the regulation of the focusing. At the back, there is a vertical brass support in which a third microscope can be inserted. This last microscope is used both for the comparator and the dividing machine. These microscopes are equipped with a micrometer screw with a half millimeter pitch and divided in 250 parts, which was used to measure the differences between the microscopic coincidences of the measurements. Once that the extremities of the samples are placed with microscopic coincidence, in other words, so that when observed with the microscope, the extremities of the samples match, through the micrometric screw is possible to note and measure differences of the order of a thousandth of a millimeter.

Brass standard weight of cylindrical shape with1 kilogram mass button. Matched with a weighing scale, it permits the calculation for comparison of mass-weight of the object under examination. In the Deleuil’s laboratory in Paris, where the weighing scale addressed to Modena Dukedom was under construction, were compared the standard brass kilogram stored by the Ministry of Intern and a kilogram of the same material manufactured by Deleuilin order to judge the sensibility of the realized weighing scale. Later, it was done the comparison between the sample n. 2 realized by Deleuil and the samples realized for Modena. The one of Deleuil was ¾ of milligram heavier than the kilogram of the Ministry. All the comparisons were done in Paris in the presence of Giuseppe Bianchi, who arrived in Paris to learn the assembly and the use of the delicate and precise instruments that there had been just manufactured. On the 18th of January 1851, once the prototypes arrived in Modena, the standard kilogram samples were compared.

Heads (à bouts) and sectors (à traits) standard meter divided in decimeters and the first decimeter also in centimeters and millimeters. It permits to effect measurements of samples of length by bringing the meter to the sample to measure and taking the length. Three standard meters made by Perreaux (cost 100 French Franc each) were compared in the Paris Observatory using a comparator manufactured by Henri Prudence Gambey.

Heads (à bouts) and sectors (à traits) standard meter divided in decimeters and the first decimeter also in centimeters and millimeters. It permits to effect measurements of samples of length by bringing the meter to the sample to measure and taking the length. Three standard meters made by Perreaux (cost 100 French Franc each) were compared in the Paris Observatory using a comparator manufactured by Henri Prudence Gambey.

Standard weight of cylindrical shape with button of 1 kilogram mass. Matched with a weighing scale, it permits the calculation for comparison of mass-weight of the object under examination.