Itinerary edited by SAPIENZA UNIVERSITY OF ROME

Giovanni Battista Grassi was a man of great biological culture. His interests ranged from the study of termite societies, to eel migration and to the identification of the malaria vector. He was a passionate researcher and university teacher who received numerous prizes and awards.

Giovanni Battista Grassi was born in Rovellasca, a small rural village in the Como province (northern Italy), on 27th March 1854, from a prestigious family of land owners. After primary and middle school, he attended the “Regio Liceo Volta” (Royal Upper School) in Como, where he graduated in 1872.

Between 1872 and 1878 he attended the Faculty of Medicine at the University of Pavia, lodged at the Ghisleri College. His teachers included some of the most prestigious Italian researchers.

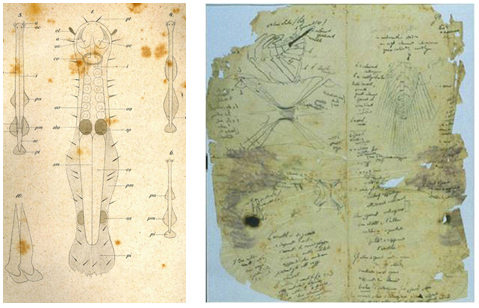

He first started research as a student, with the study of helminths, human parasites. In particular, he identified new Italian species of Nematodes causing forms of anaemia in cats and the human species (ancylostomiasis), analogous to the Egyptian chlorosis.

After graduating in medicine, he decided to dedicate himself to biological and zoological research and soon achieved significant results. He joined prestigious European research institutes, working alongside some of the most authoritative scientists of the time.

Together with Kleinenberg, at the Stazione Zoologica (biology research centres) of Messina and Naples (1878-1879), he identified Chaetognatha as a separate phylum of invertebrates.

During his German period (1879-1882), in Heidelberg and Würzburg, he worked in the laboratories of Gegenbaur, Bütschli and Semper, where he developed an evolutionist approach and refined his training as a cytologist of protozoa. In Germany, Grassi began drafting "Lo sviluppo della colonna vertebrale nei pesci" (The development of the vertebral column in fish).

In 1883, at just 29 years old, he was appointed professor of Zoology, Comparative Anatomy and Physiology at the University of Catania. His important research earned him an international praiseas a veritable King Midas of zoology, capable of turning any biological subject he touched into gold.

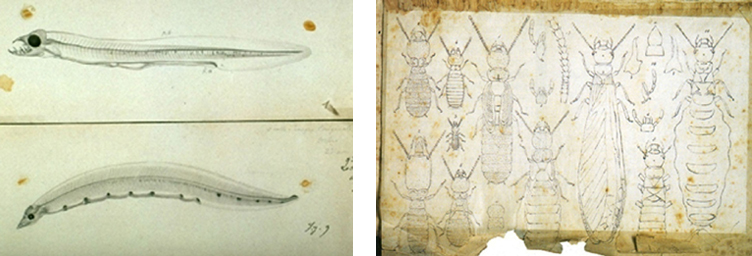

In 1892-93 he was the first to observe the metamorphosis of a leptocephalus into an eel, contributing towards the understanding of the reproductive cycle of eels.

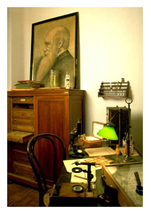

He discovered, with Koenenia mirabilis, named after his wife, Maria Koenen, a new order of arachnids, the Palpigrades. He associated the capacity to digest wood in termites with the presence of flagellates in their intestine. He also studied the determination of castes in Italian termite species.

These studies earned him the prestigious Darwin Medal of the Royal Society of London in 1896.

On the wave of his international fame, in 1895 he was granted a transfer to the University of Rome, where he taught Comparative Anatomy and, from 1903, Agrarian Entomology, which was taught for the first time at the University.

In Rome for several years a group of important malariologists had operated, focusing on the problem of malaria from a clinical point of view: the pathologist Ettore Marchiafava and his pupil Amico Bignami, the hygienist Angelo Celli and the clinician Giuseppe Bastianelli. In 1896, Grassi joined this group of scientists as an entomologist, for the identification of the vector of the malaria plasmodium.

Between 1900 and 1902 Grassi carried out important fieldwork research on malaria, which focused on finding a solution to malaria in Agro Portuense (Fiumicino) near Rome and the Capaccio plain (Paestum) in southern Italy.

In the Spring-Summer of 1900, together with Bastianelli, he was involved in Manson's experiment, conducted in the Castelfusano plain, near Ostia (Rome), regarding the functionality of a "mosquito-proof" construction.

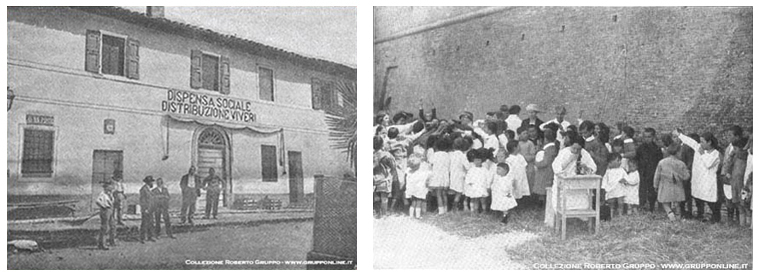

In the Summer-Autumn of 1901, Grassi and three of his students moved to the mouth of Tiber river, in the malarial area of Porto reclamation project (today Fiumicino), where he set-up a laboratory on the first floor of the Social Dispensary. The medical charts of this research project are conserved in the Grassi Archive of the Comparative Anatomy Museum.

He also suggested that the Italian Parliaments should launch a chemical protection campaign which contemplated the administration of quinine. The campaign was launched in 1901 and was concluded after the reclamation of malarial areas was completed.

On 28th November 1898, in a note to the Accademia dei Lincei, Grassi declared that he had obtained experimental proof of the transmission of the parasite and the identification of the mosquito species as a vector for humans. On 31st December of the same year, in India, in an article in the Annales de l’Institut Pasteur, the British Doctor R. Ross (1857-1932) demonstrated that the transmission of malaria in birds was linked to the parasite's development both in the vertebrate host and in the mosquito, and that the latter was also capable of infecting other birds. He hypothesised a similar malaria transmission mechanism in humans. Ross was already aware of the results obtained by Grassi, thanks to a report sent to him by the doctor E. Charles, a guest at Grassi's laboratory in 1897-98. Ross began a defamatory campaign in order to claim priority in the discovery of the malaria transmission mechanism. In 1902 Ross was awarded the Nobel Prize for Medicine.

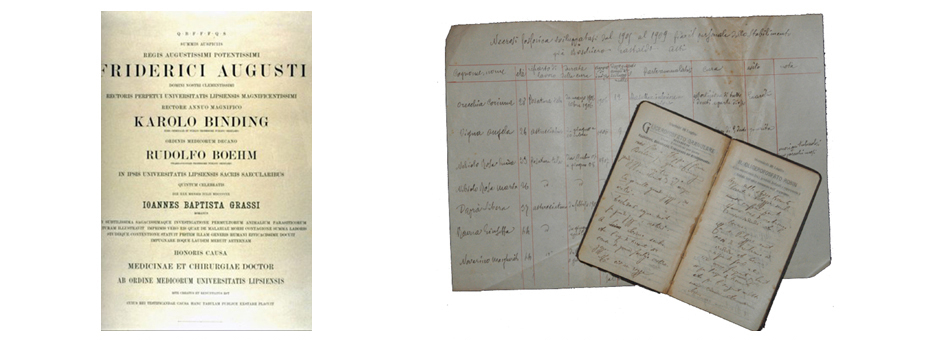

In spite of this, in many circles the idea prevailed that the Nobel Prize should have been awarded to the Italian parasitologist, and in 1910 the prestigious Leipzig University awarded Grassi the Laurea Honoris Causa for his “subtilissima sagacissimaque investigationes” on malarial contagion, underlining the preeminence (in primisvero) of his work.

Disappointed over the Nobel Prize affair, Grassi decided to give up his studies on malaria and to dedicate himself to other issues in the field of social medicine (phosphoric necrosis and alpine goitre) and entomology (sandfly and grape phylloxera).

In 1917 Grassi returned to malarial research, given the spread of the disease after the First World War.

In particular, he attempted to resolve the mystery of anophelism without malaria. As a solution, Grassi hypothesised the existence of a morphologically indistinguishable "biological race" of Anopheles, which does not bite humans but only animals. This hypothesis was confirmed by the studies of Falleroni (1926), where six species of the Anopheles maculipennis species complex were identified, only two of which are malaria vectors.

Grassi continued with his studies on malaria and teaching, and he was carried to the classroom in a wicker armchair transformed into a sedanchair, until his death in Rome on 4th May 1925, while he was revising his own manuscript on the biology of Anopheles superpictus mosquitoes.

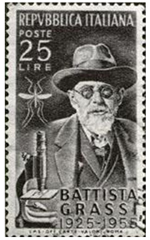

During his career Grassi obtained numerous medals and awards from all over the world. Squares, roads, institutes and hospitals have been named in his honour. In 1955, on the thirtieth anniversary of his death, Poste Italiane issued a 25 Lire stamp in his honour.

Examples of prizes and awards:

1896 - Darwin Medal of the Royal Society of London

1896 - Official of the Order of Saints Maurice and Lazarus

1897 - Gold Medal of the Accademia Nazionale delle Scienze ("National Academy of the Sciences")

1897 - Member of the Accademia Nazionale dei Lincei

1908 - Senator of the Kingdom

1910 - Cavour Prize

27th March 1854 Giovanni Battista Grassi was born in Rovellasca, a small rural town in the Como Province

1872-1878 he attended the Faculty of Medicine at the University of Pavia, lodged at the Ghisleri College; he was taught by some of the most important Italian researchers

1879-1882 during his German period in Heidelberg and Würzburg, he worked in the laboratories of Gegenbaur, Bütschli and Semper, where he developed an evolutionist approach and refined his training as a cytologist of protozoa. In Germany, Grassi began drafting "Lo sviluppo della colonna vertebrale nei pesci" (The development of the vertebral column in fish).

1883 he was appointed Professor of Zoology, Comparative Anatomy and Physiology at the University of Catania

1892-93 he was the first to observe the metamorphosis of the leptocephalus into an eel, contributing towards the understanding of the reproductive cycle of eels

1895 he was granted a transfer to the University of Rome to teach Comparative Anatomy

1896 he was awarded the prestigious Darwin Medal of the Royal Society of London

1896 Grassi joined a group of important malariologists, who focused on the problem of malaria from a clinical point of view, as an entomologist for the identification of the vector insect of the malaria plasmodium

1897 he was appointed member of the Accademia Nazionale dei Lincei

1903 he began teaching Agrarian Entomology, which was taught for the first time at the University of Rome

1908 he was appointed Senator of the Kingdom

1910 Honorary degree from the ancient and prestigious University of Leipzig, with specific reference to the discovery of the malaria vector

4th May 1925 he died in Rome while revising his own manuscript on the biology of the Anopheles superpictus mosquito

Grassi & malaria: the steps

1888 In Catania Grassi had already begun to study malaria in birds, identifying and describing its sporozoa.

2nd October 1898 As an entomologist, he recognised that only 3 species of mosquitoes (Anopheles claviger, and two species of Culex) might be involved in the transmission of malaria.

6th November 1898 In collaboration with Bignami and Bastianelli, he allows a volunteer to be bitten by infected mosquitoes. The volunteer contracted malaria.

28th November 1898 Excludes Culex as a possible vector of malaria in humans and limits his investigation to Anopheles claviger (sin. A. maculipennis).

4th December 1898 A non-malarial man is bitten by deliberately infected A. claviger and contracts malaria.

22nd December 1898 Provides a detailed description of the plasmodium cycle, both in humans and mosquitoes.

4th June 1900 His important work “Studio di uno Zoologo sulla Malaria” (A zoologist's study on malaria) is published.

Como

Como  Pavia

Pavia  Messina

Messina  Naples

Naples  Heidelberg

Heidelberg  Würzburg

Würzburg  Catania

Catania  Rome

RomeMajori G. (2012). Short history of Malaria and its eradication in Italy with short notes on the fight against the infection in the Mediterranean basin. Mediterranean Journal of Hematology and Infectious Diseases, 4(1).

Cox F. E. (2010). History of the discovery of the malaria parasites and their vectors. Parasites and Vectors, 3(1), p. 5.

Capanna E. (2008). Battista Grassi entomologist and the Roman School of Malariology. Parassitologia, 50, p. 201-211.

Capanna E. (2006). Grassi versus Ross: who solved the riddle of malaria? International Microbiology, 9, p. 69-74.

Capanna E. (2006). Battista Grassi: a zoologist for malaria. Contributions to Science, 3, p. 187-195.

Capanna E., Mazzina E. (1998). Il fondo archivistico Grassi presso il Museo di anatomia comparata dell'Università di Roma "La Sapienza". Medicina nei secoli, 10(3), p. 433-445.

Corbellini G., Merzagora L. (Eds.), (1998). La malaria tra passato e presente (p. 49-61). Roma: Miligraf.

Fantini B. (1998). Introduzione. In Grassi B., Studi di uno zoologo sulla malaria. Firenze: Giunti.

Capanna E. (1996). G. Battista Grassi: uno zoologo per la malaria. Parassitologia, 38(1), p. 5-22.

Fantini B. (1992). Biologie, médecine et politique de la santé publique: l'exemple historique du paludisme en Italie (Tesi di Dottorato in Scienze Storiche e Filologiche, Ecole pratique des Hautes Etudes, Paris, La Sorbonne).

Derksen W., Scheiding H. (1965). Giovanni Battista Grassi. Index Litteraturae Entomologicae. Serie 2: Die Welt-Literatur uber die gesamte Entomologie von 1864 bis 1900. (p. 192-194). Berlin: Deutsche Akademie der Landwirtschaftswissenschaften.

Foster W. (1965). A history of parasitology (p. 84, 103, 170, 184 s.). Edinburgh and London Livingstone.

Corti A. (1955). Nel centenario della nascita di Battista Grassi. Studia Ghisleriana, 41, p. 41.

Cotronei G. (1954). Lo spirito scientifico e l'opera parassitologica di Battista Grassi. Rivista di parassitologia, 15(4), p. 177-189.

Corradetti A. (1954). L'opera protozoologica di Battista Grassi. Rivista di parassitologia, 15 (4), p. 190-199.

Biocca E. (1954). L'opera elmintologica di Battista Grassi. Rivista di parassitologia, 15 (4), p. 200-213.

La Face L. (1954). Gli studi entomologici di Battista Grassi. Rivista di parassitologia, 15 (4), p. 214-240.

Heid M. L. (1944). Uomini che scompaiono. Firenze: Sansoni.

De Kruif P. (1940). Ross contro Grassi. In De Kruif P. I cacciatori di microbi. (p. 329-352), Milano: Mondadori.

Pazzini A, Fedele M. (1935). Biobibliografia. G. B. Rivista di biologia, 19, p. 126-169.

Cotronei G. (1927). Battista Grassi nella biologia del suo tempo. Ricerche di morfologia, 7, p. 1-18.

Silvestri F. (1927). Commemorazione di Battista Grassi. Memorie della R. Accademia dei Lincei, 2, p. IX-LXIII.

Fedele M. (1926). L'opera e gli insegnamenti di Battista Grassi. Bollettino della Società dei naturalisti in Napoli, 38, p. 59-93.

Pierantoni U. (1926). Battista Grassi. Atti dell'Accademia delle scienze di Torino, 61, p. 231-237.

Dobell C. (1925/07/18). Prof. Battista Grassi. Nature, p. 1-4.

Janicki C. (1925). Giovanni Battista Grassi. Eine grosser Zoologe und Parasitologe Italiens. Die Naturwissenschaft, 14(12), p. 225-231; (13), p. 261-269.

Verney L. (1925). Giovanni Battista Grassi. Entomological News, 36, p. 224.

Montalenti G. (1925). Battista Grassi. Arch. di storia della scienza, 6, p. 194-196.

(1925). Onoranze a Battista Grassi. Roma, Tipografia del Senato di G. Bardi.