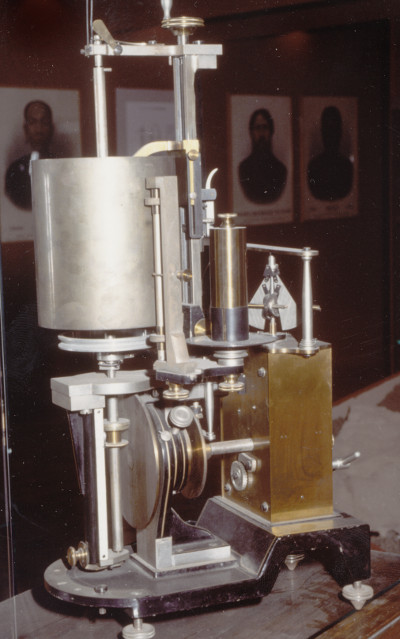

His extensive knowledge of Greek authors led him to focus on philosophy and he published his first work, Usiologia ovvero scienza dell'Essenza (1868), on ancient philosophies of pre-Roman Italic populations. Influenced by the positivist philosophical ideas of his time, he took his first steps towards psychology based on experimental foundations. He became the first in Italy (1873) to propose his study on physiological foundations, in a work that anticipated, by a year, the classic by Wundt (1832-1920): Grundzüge der physiologischen Psychologie. However, this was just the beginning, as Sergi felt the need for a broader and more extensive knowledge. Over the following few years he dedicated himself to studying mathematics, physics, anatomy and physiology. He then set up a laboratory with equipment for the recording of empirical data, in accordance with the latest school of thought of European experimental psychology, for the establishment of objective criteria in the study of psyche and human behaviour. In 1889 he established an experimental psychology laboratory at “La Sapienza” University in Rome, annexed to the Institute of Anthropology. Independent teaching soon developed from this initial nucleus, followed by an independent institute of psychology, directed by one of his most illustrious students: Sante de Sanctis (1862-1935). At this stage he had already elaborated an integral vision of man in nature and its laws, based on the great concept of Vico, underpinned by the union of philology with philosophy for the history of humankind. However, he believed that men are animals, or rather that men are the way they are due to the nature in which they live and from which they derive. He believed that it is possible to achieve knowledge of mankind by studying it in its development in nature, which is an essential part of mankind. He went on to develop this concept during his long academic career. Step by step, he overcame numerous difficulties and extensive opposition, equipped with modest yet adequate means. In earnest, he gradually proceeded to set up the Institute of Anthropology, which brought prestige to the University of Rome. He gradually improved it by adding material characteristic of a large museum, thus transforming it into one of the first of its kind in Europe in terms of the richness and rarity of its collections, mostly donated to him as personal gifts, and integrated with the Società Romana di Antropologia (1893). He published the Acts of the latter, which were then transformed into «Rivista di Antropologia» (Anthropology Magazine) and became the school's publication: it was about the history and development of anthropological sciences in Italy and was renowned throughout the world. Both before and after the foundation of the Società di Antropologia, he has contributed towards the foundation and direction of other scientific periodicals, including «Rivista di Filosofia Scientifica», «Rivista di Sociologia», «Rivista di Pedagogia e Scienze affini». In 1916, upon reaching the age limit, he resigned from official teaching and was appointed professor emeritus of the Faculty of Sciences at the "La Sapienza" University of Rome. He continued to work until late in life and, aged over ninety, he published works rich in new ideas and original concepts. His numerous written works document the sheer versatility of his scientific production and the fertility of his ideas in the fields of psychology, ethnology, biology, pedagogy and sociology. He suggested new orientations, created innovative methods and doctrines regarding mankind in diverse biopsychological aspects.

He formulated the theory of stratification of character, which became a fundamental principle of psychoanalysis, later extended from psychology to psychopathology and criminology, deepening understanding on the evolution process of psychic phenomena. He created the craniological descriptive method, which paved the way towards a correct morphological evaluation of the cranium. He also identified the Mediterranean “race” and traced a general systematic structure of humanity. In 1886, he proposed the construction of an anthropological observatory for the creation of a biographic chart of students, to study the somatic-physio-psychological traits of individuals during growth, for the protection of health and greater participation of everyone in social life. He took part in debates on issues of general interest, in particular regarding education schemes.

Some of the most significant findings and collections include: