The Development of the University during the Nineteenth Century

The Civic Council of Cagliari first submitted its request to offer a Scheme of Study to the Parliament during Viceroy De Cardona’s Presidency (1542-1543). A subsequent joint request by the Royal, Clerical and Military S tamenti (each of the branches of the Sardinian parliament) was submitted during De Herendia’s Presidency (1553-1554). A final request was also filed during Viceroy Don Giovanni Coloma De Elda’s Presidency. Despite the Civic Council’s commitment to covering all the costs, the project eventually ground to a halt.

Fifty years later, during Viceroy Antonio Coloma’s Presidency (1602-1603), a formal appeal was lodged in order to establish an Estudi y Universitat publica in Cagliari. The Royal consent and the papal authorization were issued respectively in 1604 and 1607, whereas the right to charter was issued on 31st October 1620.

The first Scheme of Studies was structured according to the Spanish model and the University of Lérida in particular. The Archbishop of Cagliari was appointed as the Chancellor of Studies while the City Councillors elected the University Chancellor every three years. The University Charter was signed on 1st February 1626 and the Faculties of Theology, Liberal Arts, Philosophy, Law and Medicine were established. The first Chancellor was Cosma Escarxoni, Canon of the Cagliari Cathedral and General Vicar. The following year he stepped down and the new Archbishop Ambrogio Machin was appointed. The patron saint of the new Universidad became the Virgin Mary along with the Sardinian saints Hilarius, Saint Lucifer of Cagliari and Saint Eusebius, which are all represented on the coats of arms of the University.

The university soon had to face many challenges. The conflict between the Archdiocese and the City Council and the institution’s overriding financial difficulties contributed to delay the activities of the Studium Generalis Kalaritanum. Although the professors were well-respected scholars, they were not paid on a regular basis and often interrupted their teaching commitments, deserting their lectures.

In 1682, the Spanish government tried to tackle a severe economic crisis due to ongoing famine and pestilence by demanding the direct payment of all the fees of all the universities under the Spanish Crown. This led to the closure of many chairs in several universities, including Cagliari’s.

In 1720, Sardinia came under the rule of the House of Savoy, which overlooked the university issue until 1755, when King Charles Emmanuel III of Sardinia ruled for a commission to be appointed to examine the financial situation of the University of Cagliari and propose adequate measures for its reorganisation.

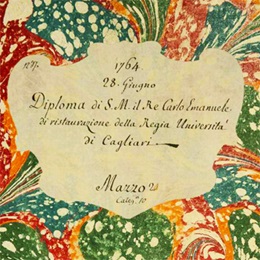

The appointed Commission rapidly carried out its mandate but the Government delayed taking action. In 1759, the government established the School of Surgery and appointed Michele Plazza as its director; he continued to lecture at the University of Turin as well. However, the first real input for the reform of this institution came with the appointment of Giovanni Battista Bogino as Secretary of State for Sardinian Affairs. Charles Emmanuel III signed the new Statute of the Academia calaritana on 28th June 1764.

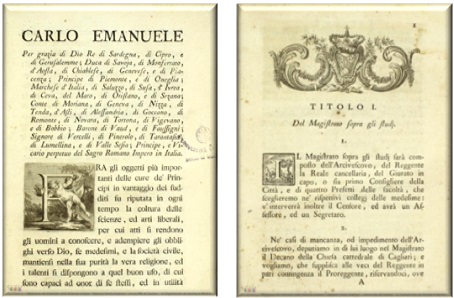

In compliance with the new Statute issued in 1764, the Chancellor was to be replaced by a collegial council called the Magistrate of Studies. This council’s members included the Archbishop of Cagliari, the Regent of the Royal Chancellery, the Chief Councillor of the City, the Prefects of the four Colleges (now the Deans of each Faculty), the Censor and the University Secretary. The main objective of the Magistrate was to oversee the programmes offered by the University and guarantee general order. This soon resulted in the resolution of the conflict between the Archdiocese and the City Council concerning the election of the Chancellor.

In compliance with the new Statute issued in 1764, the Chancellor was to be replaced by a collegial council called the Magistrate of Studies. This council’s members included the Archbishop of Cagliari, the Regent of the Royal Chancellery, the Chief Councillor of the City, the Prefects of the four Colleges (now the Deans of each Faculty), the Censor and the University Secretary. The main objective of the Magistrate was to oversee the programmes offered by the University and guarantee general order. This soon resulted in the resolution of the conflict between the Archdiocese and the City Council concerning the election of the Chancellor.

The new teaching staff comprised both lecturers from Piedmont and young Sardinian scholars who had completed their studies at the University of Turin. Another important innovation was the construction of a new University building that today hosts the Chancellor’s Office. This building was designed by Saverio Belgrano from Famolasco and was officially opened on 1st November 1769. In 1792, the University library was also built.

The new teaching staff comprised both lecturers from Piedmont and young Sardinian scholars who had completed their studies at the University of Turin. Another important innovation was the construction of a new University building that today hosts the Chancellor’s Office. This building was designed by Saverio Belgrano from Famolasco and was officially opened on 1st November 1769. In 1792, the University library was also built.

The first few years of the ‘new’ university were characterised by important achievements in the fields of law and mathematics. Conversely, the School of Medicine did not attract many students, much to the disappointment of the House of Savoy government’s, which aimed to train new doctors who could work in many of the island’s villages. Hence, several measures were taken to encourage more young Sardinians to study medicine and surgery. New teaching tools and materials were also made available.

Towards the end of the seventeenth century, there was a renewed interest in medical studies thanks to anatomist Francesco Antonio Boi and Pietro Antonio Leo, Professor of Medical Clinic. Thanks to the former’s intervention, the University received a donation of the sculptor Clemente Susini’s wax anatomical models, whereas the latter helped to introduce the smallpox vaccine in the Kingdom of Sardinia.

Since the second half of the 18th century, the students at the University of Cagliari had become more aware of political and social issues, and liberal ideas had spread to many European universities. Public displays of such a liberal impulse included the conspiracy of Palabanda in 1812, which also saw the involvement of professors and members of the university’s administrative staff.

During the Restoration period, the House of Savoy government became actively involved in the reorganisation of the university, especially the School of Medicine, to the extent that Surgery was made an independent school. At the undergraduate level, students had to complete a traineeship at the Civil Hospital. After graduating, they had to complete a one-year internship at a hospital of their choice or a two-year internship at a doctor’s surgery. Only after that could they be allowed to practice medicine.

New chairs were added in all faculties and in 1842 new rules were introduced. For instance, university professors were forbidden to carry out any other professional activities that could hinder their lecturing activities. Most importantly, the Chancellor was reinstated and, with the so-called “Perfect Fusion” in 1848, the Magistrate of Studies was replaced by the Secretary of State for Public Education.

After the unification of Italy, the Matteucci Law of 1862 ruled that Italian universities had to be subsumed under two groups, class A and class B, which penalised class B institutions (including Cagliari). Some professors attracted to working in better facilities and obtaining higher salaries decided to transfer to class A universities. Despite the many attempts to raise the status of the University of Cagliari, on the part of teachers and the student body alike, the “demotion” of Cagliari to class B would last forty long years. Nonetheless, it never ceased to carry out its institutional activities and kept the quality of its scientific publications high. It also continued offering its students and lecturing staff new infrastructure such as the Botanical Garden, the new Anatomy building, an extended Museum of Archaeology, Minerals and Material Culture. It also enlarged the book collection of its main library.

At the official opening ceremony of the academic year today, the Chancellor’s speech usually includes a review of the most significant changes the University of Cagliari underwent during the 20th century.

During the first three decades of the century (1908-1938), new building plans were carried out involving the restoration of Palazzo Belgrano, the construction of the Science Building, Biology Institute, Paediatric Clinic, Anatomy Institute and the Biology Station in Ponte Vittorio.

In 1915, the university planned to create a university campus but the project was temporarily shelved due to the outbreak of World War I. After the war, the university resumed its activities and strove to reclaim its cultural prominence as quickly as possible.

However, real change would only come about on 30th September 1923, when the Gentile Law allowed Italian universities greater administrative and operational autonomy. Over the course of this reform, the University of Cagliari was able to reorganise its faculties by adopting a new Statute. In 1926, the Faculty of Humanities was reinstated, as it had been closed in 1859.

However, real change would only come about on 30th September 1923, when the Gentile Law allowed Italian universities greater administrative and operational autonomy. Over the course of this reform, the University of Cagliari was able to reorganise its faculties by adopting a new Statute. In 1926, the Faculty of Humanities was reinstated, as it had been closed in 1859.

When the Fascist Regime came to power, the University of Cagliari and other Italian universities were put under the administration of an external commissioner, and Giovanni Cao di San Marco was appointed Commissioner for the academic year 1935-1936.

In 1938, the Fascists’ pro-Aryan policy imposed the enforcement of racial laws discriminating against Jewish citizens and some Jewish professors were fired by the University.

The outbreak of World War II led to several air raids against the city. Consequently, many people chose to move inland and the university once again had to suspend activity. Only when the Armistice was signed on 8th September 1943 could the University of Cagliari, amid myriad difficulties, rapidly resume its normal activities.

Link

Tasca C., Rapetti M., Todde E. (Eds.) (2016). Archivio storico dell’Università di Cagliari. Guida ai fondi documentari. Cagliari.

Ferrante C. (2013). Cagliari e Lerida, il modello di fondazione di uno Studio municipale. In Le origini dello Studio generale sassarese nel mondo universitario europeo dell'età moderna. Bologna.

Schirru M. (2010, aprile). L'Università degli Studi di Cagliari e il complesso architettonico sul Balice (Vol. 14, p. 371-405). In Annali di storia delle università italiane, Bologna : CLUEB. Disponibile da http://www.cisui.unibo.it/frame_annali.htm.

Merlin P. (2010). Progettare una riforma: la rifondazione dell'Università di Cagliari (1755-1765). Cagliari : Aipsa.

Anatra B., Nonnoi G. (2007). Università degli Studi di Cagliari (Vol. 3, p. 309-322). In G. P. Brizzi, P. Del Negro, A. Romano (Eds.). Storia delle Università in Italia, Messina : Sicania.

Bullita P. (2005). L'Università degli Studi di Cagliari. Dalle origini alle soglie del Terzo Millennio (memorie e appunti). Oristano.

Sorgia G. (1986). Lo Studio generale cagliaritano. Storia di una Università. Cagliari : Università degli studi.

Lattes A., Levi B. (1909-1910). Cenni storici sulla regia Università di Cagliari. In Annuario della Regia Università di Cagliari. Cagliari.

Guzzoni Degli Ancarani A. (1897-1898). Alcune notizie sull’Università di Cagliari. In Annuario della Regia Università di Cagliari.

Dessì Magnetti G. (1879). Notizie storiche sulla regia Università degli Studi di Cagliari. Cagliari.